I talked about how the whole idea started, how we selected the school project and how we kicked off the experiment. In this post you will find the whole experience report, the results of the experiment and some conclusion we feel we could draw.

The experience report

The stand-up routine triggered very quickly

some interesting behaviors right from Sprint 1.

Each team had their stand-up meeting on

Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays from 8.45 to 9.00, where each kid

learned to explain:

●

What did I do since our last

stand-up meeting that helped my team meet the Sprint Goal?

●

What will I do today to help my

team meet the Sprint Goal?

●

Do I see any impediment that

prevents me or my team from meeting the Sprint Goal?

In the same days they got one hour to

actually execute the tasks they had pulled into work.

The self-organizing daily planning was

pretty rapidly received and understood by the kids, even though it was a

completely new practice for them. It even affected school entrance punctuality

in a very positive way: all kids tended to arrive on time to attend the

stand-up and not to lose the opportunity to speak up.

As described in the previous post, each

backlog item consisted in representing one of the 20 Italian regions on

construction paper, visualizing morphological characteristics, hydrography and

main cities; the team which pulled the story had to study everything concerning

the specific learning object, including economic activities, relevant

historical figures, monuments, customs and traditions, without this information

was presented or explained in any way.

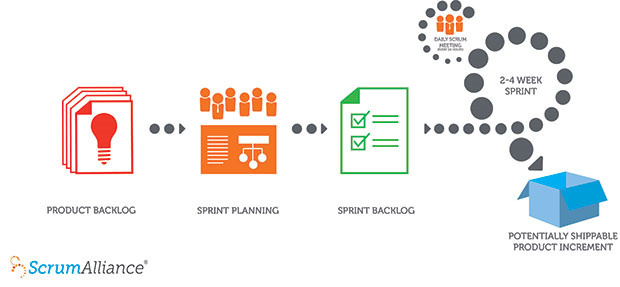

Each Sprint was three weeks long and ended

with a Sprint Review where each team had to show what they learned and created

during the Sprint to the teacher and the rest of the class. The shape they

created on the construction paper was also integrated on the big map to get a

truly potentially shippable product at the end of each Sprint, which all teams

contributed to. Many even deepened the subjects presented in the school book with

additional researches and volunteer studies.

The demo was organized directly by the

students in an autonomous and simple fashion, by splitting tasks inside each

team. Each kid had his/her specific role in the product presentation, even

though everyone was able to discuss any aspect concerning the region under

review: this was yet another proof point for us that the ability to

self-organize is kind of natural and desirable even for the youngest.

After the joint Sprint Review, each team

had their own Sprint Retrospective to encourage a collective self-reflection

both on the quality of the work done and on the interpersonal dynamics which

characterized the path towards the delivered product at the end of Sprint.

The retrospectives, held before starting

the new Sprint, were facilitated in a lightweight way (e.g. using

straightforward activities like Mad-Sad-Glad) to allow the kids to point out more

easily the key items to reflect upon. Usually each retrospective had an

individual reflection time first and then a team sharing to give everyone equal

air time and avoid stronger characters to take the monopoly of the

conversation.

The highest voted improvement item by the team triggered a team commitment to one or more improvement actions to execute in the coming Sprint.

The highest voted improvement item by the team triggered a team commitment to one or more improvement actions to execute in the coming Sprint.

For instance, in the first Sprint, one of

the teams had wrongly interpreted the information on the atlas map and included

inside Veneto (Venice region) a big lake where you are supposed to

find Dolomites! During the retrospective the team had the chance to reflect

that, possibly, studying the region first, before representing it graphically

on the construction paper, would be a better option (before the end of the

school year they also managed to fix the mistake effectively!).

It was extremely interesting for us to

notice how, thanks to regular retrospectives, each team developed a

self-consciousness of being one team with one common goal.

At the beginning, some students, usually poorly disposed to stay focused and participate actively to the school activities, tended to isolate during the daily working time or to group with classmates from other teams, who had the same low commitment or the same poor inclination to teamwork.

These aspects started to emerge during the Sprint retrospective and some kids, publicly confronted by their teammates, first reacted with denial and even burst into tears, accusing the others of not involving them. Every team has to go through a Storming phase!

At the beginning, some students, usually poorly disposed to stay focused and participate actively to the school activities, tended to isolate during the daily working time or to group with classmates from other teams, who had the same low commitment or the same poor inclination to teamwork.

These aspects started to emerge during the Sprint retrospective and some kids, publicly confronted by their teammates, first reacted with denial and even burst into tears, accusing the others of not involving them. Every team has to go through a Storming phase!

However these heated debates brought their

fruits.

The students, who did not show commitment, realized that their disengagement wasn’t going unnoticed; at the same time the “hard-working part” of the team acquired a higher sense of responsibility in engaging their teammates, who probably wanted (and needed) to be a bit more stimulated and supported in their learning journey.

The students, who did not show commitment, realized that their disengagement wasn’t going unnoticed; at the same time the “hard-working part” of the team acquired a higher sense of responsibility in engaging their teammates, who probably wanted (and needed) to be a bit more stimulated and supported in their learning journey.

In some cases, this sense of responsibility

took some particularly capable and mature student to play a mentoring role

towards the kids who showed some learning difficulties, naturally nudged by the

framework to practice “cooperative learning” and “learning by doing”.

In a wonderful talk to a group of young students, Simon Sinek says: “Learn by practicing helping each other. It will be the most valuable thing you ever learned in your entire life”. And this was exactly what our kids were experimenting.

In a wonderful talk to a group of young students, Simon Sinek says: “Learn by practicing helping each other. It will be the most valuable thing you ever learned in your entire life”. And this was exactly what our kids were experimenting.

The fact that no one was a formally

recognized leader, nor could ever be, put a stop to some usually strong

leaderships, who used to dominate the class. This boosted instead who more

often preferred to follow others. Interpersonal dynamics enjoyed great benefits

during the journey, especially due to the need for the team members to

necessarily achieve some form of group consensus, in order to move forward and

progress in the work.

As the northern regions were inserted into

the map and started to connect with each other, a discrepancy in the quality of

the work among the different teams and few integration issues became obvious.

For instance, the coloring looked in-homogeneous, while rivers crossing over multiple regions flew incongruently. It was so visible, that the kids realized that they needed to collaborate across teams, especially to define the borders between different regions and to agree on the execution of common areas to multiple regions. They also co-created a common Definition of Done.

For instance, the coloring looked in-homogeneous, while rivers crossing over multiple regions flew incongruently. It was so visible, that the kids realized that they needed to collaborate across teams, especially to define the borders between different regions and to agree on the execution of common areas to multiple regions. They also co-created a common Definition of Done.

This contributed greatly to improve the

work execution and the general quality of the unique product (the big map of

Italy) that all teams realized they had to collaborate to produce: the power of fast

feedback loops and early integration :)

At the end of the school year, the last

region to complete was Campania, their home region. In that specific case the

backlog item was divided into smaller chunks (five provinces) to allow all

teams to collaborate, but still keep their own Sprint backlog.

Both half-way and at the end of the year,

all parents were invited to the Sprint Review to experience first-hand what

their children were doing and learning. The reactions were enthusiast to say

the least: they said that their kids were telling them what they did at school, but

seeing them in action in a fully autonomous and self-organized way was a source

of great satisfaction for them.

In both cases the day ended with a celebration in the classroom, where the whole group could taste delicious food and cakes which the kids and their parents had prepared at home and brought to school.

In both cases the day ended with a celebration in the classroom, where the whole group could taste delicious food and cakes which the kids and their parents had prepared at home and brought to school.

Results

We analyzed the results of the experiment

through collection of both subjective and objective data.

First we asked kids and their parents

to fill in a multiple choices questionnaire to evaluate the experience compared

to a similar course they had to study in the previous years.

The idea was to look at what happened from

the perspective of the students and the perception of their parents.

Here is the list of questions we proposed:

Since I started using Scrum and compared to

the geography class during last school year:

- I learned much less/less/about the same/more/much more

- I understood the task the teacher was asking me to do much

less/less/about the same/more/much more

- I had fun much less/less/about the same/more/much more

- I felt motivated much less/less/about the same/more/much more

- I collaborated with others much less/less/about the

same/more/much more

- I felt autonomous much less/less/about the same/more/much more

- I organized my work much less/less/about the same/more/much

more

- I feel satisfied of what I have achieved much less/less/about

the same/more/much more

- If it was solely up to you to decide, would you continue using

Scrum at school? Definitely No/No/Doesn’t matter/Yes/Definitely Yes

- Would you suggest Scrum to your friends inside or outside your

school? Definitely No/No/Doesn’t matter/Yes/Definitely Yes

The questionnaire for the parents contained

the same questions: we just replaced “I” with “My child”.

The results were astonishing.

More than 84% of the kids' answers were positive, including all the answers reporting "More" or "Much more", "Yes" or "Definitely yes" in the definition of "positive". The rest were basically neutral answers with less than 2% of the answers being negative.

The parents' evaluation was even more positive: 95% of the answers were positive and absolutely none was negative.

More than 84% of the kids' answers were positive, including all the answers reporting "More" or "Much more", "Yes" or "Definitely yes" in the definition of "positive". The rest were basically neutral answers with less than 2% of the answers being negative.

The parents' evaluation was even more positive: 95% of the answers were positive and absolutely none was negative.

In particular below are charts showing the

percentage of the answers for the different statements in the questionnaire for

the students and their parents.

|

| Answers from kids |

|

| Answers from kids |

|

| Answers from parents |

|

| Answers from parents |

The objective evaluation includes the

proficiency the different kids achieved in a variety of skills and disciplines analyzed from the teacher perspectives.

The data emerged at the end of the project are reported in the table below and are classified in different areas, to make them easier to read.

The data emerged at the end of the project are reported in the table below and are classified in different areas, to make them easier to read.

Relationships and Social skills

|

Before the project, the class group had already a

good level of social and relational skills, but there was a certain tendency

to privilege some friendly relationships compared to others, which were kind

of less “desired”.

The need to involve and get

consensus from others, with no chance to “impose” any decision, has clearly

sharpened the relational skills of every student, both those who are more

naturally inclined to lead and those who are more kind of “followers”.

The former ones had to learn how

to articulate their ideas more effectively, the latter ones got finally the

chance to dissent and propose, although still with hesitance, alternative

suggestions. And everything happened in a more and more collaborative

and fun environment as the time went by.

|

Respect of ground rules

|

The framework gave structure and a

feeling of rhythm and cadence to the work. This made the rules of the game

more visible, more effective and thus easier to follow, with a direct

consequence on the kids’ ability to respect ground rules about living at

school and outside the school.

|

Personal interest

|

The interest of the kids into all

activities and consequently into the studied discipline was very high

throughout the whole experiment. This gets even more relevance if analyzed in

comparison with the same discipline studied in the previous school year. The clarity of the expected

outcome and the enablers in the framework gave the possibility to constantly

reflect on strengths and improvement areas and directly act on them both on

individual and team level. As a consequence the level of ownership was always

pretty high.

|

Motivation

|

Capturing attention and stimulating motivation is usually pretty hard with a subject like geography at a primary

school.

Differently from last year and

from former professional experiences the teacher had with grade 5 students, there was no need

to motivate kids to learn this time. They just showed so much drive towards their goal and how to reach it in the best possible way, that no additional motivator

was necessary.

|

Engagement

|

The participation to the class

activities was very high. The major educational success of this activity was

determined by the high level of engagement, especially of those who were

more prone to lose focus and used to participate less.

The proposed project looked just

like a technical and graphical activity, but in reality required an accurate

study of the discipline, which the kids accomplished without even realizing it. The

strive to achieve the final result pushed them to research as much

information as possible, in order to deliver a quality product (the map)

which was easy to understand also for the classmates, who had not studied the

specific region.

|

Commitment

|

The level of commitment was simply

a result of motivation and engagement, so obviously the results were very

positive. The students who were used to achieve outstanding results, simply

excelled in the project. But most important, the kids who were used to

struggle to achieve a sufficient grade, reached educational results far above

their average, also thanks to the support and help from their teammates.

|

Planning and time management

|

One of the biggest outcomes of

this project was the improvement in terms of ability to plan the work

and time management: at the end of the year all the students reached an outstanding

level of autonomy and self-organization.

Even the kids, who had more

troubles in finding an effective time management approach, had the chance to

catch up thanks to the intrinsic focus and the teamwork.

|

Competence level

|

The class group which experimented

this project had already pretty high average level of proficiency and grades.

However the multiple elements, emerging from the project, contributed to determine a generally much

more positive grade compared to the results achieved by the same students in

previous school years.

It is interesting to highlight that the

results achieved have been even more positive for the students who had already outstanding

grades.

Those who had good grades accomplished

remarkable improvements, with a greater awareness of their own abilities.

Those who barely reached a

sufficient grade had numerically better grades, but the fundamental outcome of

this experiment was an actual acquisition of new competences from all kids.

Those competences include the ones

that in the European Commission White paper “Teaching andlearning: Towards the Learning Society” are denoted as: the Know-how (skills), the Know-how-to-be (attitudes),

the Knowledge.

These are the goals to purse at

school: the students must acquire Knowledge

(Rome is the capital city of Italy; Monte Bianco is on the Alps, etc.), but

they have to acquire also, and much more than the mere knowledge, the Know-How (logical skills, intuitive skills, linguistic skills, etc.) and the

right Know-how-to-be.

Actually the most important task of the school nowadays should be to help kids learn how to learn, so that they can keep learning for the rest of

their life and the applied methodology seemed to support very much this

direction. |

Conclusion

The experiment tried to give an answer to

following questions.

Can Scrum used in education support to

create a learning experience for kids which would encompass the following?

- Being more adaptable to a kid’s specific learning needs

- Being a meaningful experience involving feelings and physical emotions

- Fostering self-development and co-education

- Training skills which are crucial in the 21st century and the school is traditionally not that good at teaching, e.g.

- self-organization

- leadership

- ability to plan

- imagination

- self-reflection

- dealing with uncertainties and the unknown

The empirical evidence of what happened

during the experience (including the observation of the behaviors naturally

nudged by the adoption of the Scrum framework) as well the collected results,

encourage a positive answer to these questions and validate the assumption that

Scrum is a powerful change engine in many different contexts.

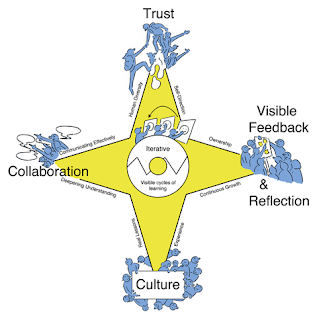

Scrum is founded on empirical process control theory, which asserts that

knowledge comes from experience and

making decisions based on what is known. Scrum employs an iterative,

incremental approach to optimize chances of success when addressing a complex

problem, a problem where solution is unknown or multi-faceted, including

learning something new.

Empirical process control has three pillars:

transparency, inspection, and adaptation. When you manage to create an

environment where the values of commitment,

courage, focus, openness and respect are embodied and lived by the Team,

the Scrum pillars of transparency, inspection, and adaptation come to life and

build trust for everyone. Then people, whether kids or adults, are capable to

learn and explore as they work with Scrum.

On top of that, the students could engage

with their classmates and their teacher in a much more human and profound way

and live an experience they will probably remember forever and tell to their

grandchildren.